|

||||||||||||||||

| virtual Studio | References | Workshops | Styles of Frames | History | Collection | Gallery | ||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

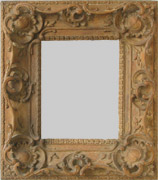

| A short round trip through the history of frames Gothic Renaissance Ludwig XIII Ludwig XIV Regency Ludwig XV Ludwig XVI Baroque (Southern Germany, The Netherlands) Baroque (Italy, Spain) Classicism Art Nouveau Classic Modern Click the picture for enlargement Introduction |

|||

|

|

|||

| The structure of the frame | |||

|

|

|

|

|

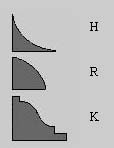

The most important frame profiles |

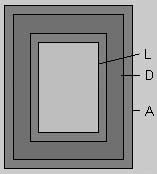

The structure of the Cassetta frame

L : Sight edge (inner edge) D : Flat frieze A : Outer edge |

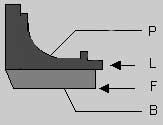

The structure of a profile frame

P : Profile frame L : Clearance F : Rabbet B : Blank frame |

|

|

|

|||

| Gothic | |||

|

In the late Middle Age the panel painting began to emancipate itself from the wall mural. The first framed panel artworks were still integrated into the painted wall architecture.

They formed a visual border to a room in which increasingly individual rules were applied. The first frameworks reached their highpoint with the carved, winged altars and retables, or altarpieces, of the fitments of the church. Also pictures for everyday rooms took over motifs from architecture, for example columns, archivolts and cornices. The picture and frame formed the “window” to another world and were sometimes additionally protected by a curtain. |

|

|

|

|

Southern Germany, Gothic Frame, 15th century

The frame is built like a window frame. The bevel cut can be clearly seen as well as the carved bead-mouldings on the sides. Model 58 |

Details of the carved bead-mouldings with bulbous baluster and angular plinth, which touch down on the bevel cut. | ||

|

|

|||

|

Renaissance

|

|||

| During the Renaissance two types of frames were developed: the architectural frame, mostly reproduced from a Greek temple facade, and the classic Cassetta frame. The architectural frame sometimes continued into the painted perspective of the picture and determined the stage-like character of the picture. The Cassetta frame is made up of three parts and consists of a dainty inner profile (the sight edge), a sturdy outer profile (the outer edge), and a recessed, broad, ornamental or single-coloured middle area, or frieze. It is a classic type of frame, which can be found again in frames of the 20th century because of its two-dimensionality. In the Renaissance and Gothic periods the gilded frame was often more expensive than the actual painting. |

|

|

|

|

Italy, ca. 1540. Aedicule or tabernacle frame with bulky base and chestnut woodwork with a polished surface. The columns are freestanding. The protruding cornice rounds of the architrave.

|

Germany, ca. 1540. Cassetta frame from the vicinity of the Cranach workshop. The inner and outer profiles are gilded; the frame side rails are decorated with knob attachments. Model 1562 |

||

|

|

|||

| Ludwig XIII / Ludwig XIV | |||

| Due to its advanced position in architecture and interior design culture, the art of frame making reached its highpoint in France in the 16th and 17th centuries. Because of the centralized culture at Court, standards developed which for many centuries set an example for the whole of Europe. In the style eras, named after the kings, the French national style “Classicism” extends into other realms, uniting Baroque and Classic elements. The development of the picture frame reflects the development in architecture and the history of art. The Baroque elements remain rational and subordinate to a transparent lineal overall concept. |

|

|

|

|

France, Ludwig XIII, profile frame, 1st half of the 17th century. Characteristic are the straight-lined ornamental areas without embellishments on the corners of the frame. The main profile is a bead moulding |

France, Ludwig XIV, profile frame, end of the 17th century. |

||

|

|

|||

| Regency / Ludwig XV / Ludwig XVI | |||

|

|

|

|

| France, Regency, profile frame, 1st half 18th century. The flat baroque strap work ornamentations break up the orderliness of the ornamental areas. The corners of the frame are embellished with foliate motifs. The diamond engraving as a background to the carved ornamentations is the visible transition from Baroque to Rococo. The principle shape is the ogee, or cyma. Model 1463 |

France, Ludwig XV, profile frame, mid 18th century. The three-dimensional decoration is raised from the under surface. The foliate mouldings are set in the corners and interconnected by an elevated band of stalks. The cyma shape as a base for the carvings is barely discernable. There are only remnants of the original gilding work left. Model 1793 |

France, Ludwig XVI, oval frame with crown, ca. 1780-1790. The baroque three-dimensional ornamentations have disintegrated and the decorated areas are again separate. Early Classical Canonical, or standard, form with egg-and-dart and bead mouldings: The basic profile is now a hollow in the external profile. The dainty ribbon loops are a reminder of the Rococo period. Model 1993 |

|

|

|

|||

| Baroque (Southern Germany / The Netherlands) | |||

| The Bavarian chief court architect, Joseph Effner (1687-1745), induced the flowering of the Regency and Rococo styles, and in doing so disengaged himself from the strict canon of the French School. After him came Francois Cuvilliés the Elder (1695-1768), also French-trained. In the Netherlands and Flanders towards the end of the 16th century, the typical black “Dutch” frame evolved from ebony furniture. As ebony is expensive, it is not processed as solid wood but as a veneer and so the profiles are kept flat. There are also simple Cassetta frames without a profile that are impressive due only to the precious ebony. In Baroque, the waved borders and embellished corner mouldings increase the sensual effect of the frame. As a replacement for ebony, dark-stained pear wood was used. Dutch frames were replicated particularly in the Alp regions. |

|

|

|

| South Germany, moulded frame, 1st half 18th century. The frame is from the vicinity of Joseph Effner (1687-1745), Bavarian chief court architect. Single-handedly crafted according to a French prototype. Typical of Effner frames are the freestanding plant stems, so-called stretchers. Model 1475 |

Alp region according to a Dutch prototype, profile frame with ripple and wave borders, |

||

|

|

|||

| Baroque (Italy, Spain) | |||

|

In art centres such as Florence, Venice, Siena and Bologna, frames developed their own language of shape and form. In the Baroque era the Canaletto moulded frame, named after Giovanni Antonio Canale (1697-1768), became especially popular and was imitated all over Europe. Typical of Spanish frames in the 16th and 17th centuries is the hard, black and gold contrast and the rough ornamentation that varies with the original patterns of Italian and French motifs. Cassetta frames are likewise adorned with a coarse, rustic decoration. There is an affinity to frames from the southern Italian area as Naples was under Spanish rule from 1504-1713.

|

|

|

|

| Italy, Canaletto frame, Venice, 1st half 18th century. Characteristic is the fine, two-dimensionality of the profile, interrupted by smooth mirrors (polished areas without ornamentation). The basic pattern is a cyma, the ornamentations being carved and in the background punched. Model 1006 |

Spain, profile frame,

end 17th century. The frame comes alive due to the hard black and gold contrast, which gives it a three-dimensional quality. The corner ornamentations are stylised trumpet shaped flowers. Model 1147 |

||

|

|

|||

| Classicism | |||

|

In Classicism (1750-1840) a characteristic, easily identifiable style of frame was developed with a three-part construction. The sight edge has a continuous cyma border with heart-shaped foliage, or bead and reel rods for decoration. Then follows the flat frieze that definitively separates the sight edge and outer edge from each other. The outer edge or profile is a broad, rising hollow decorated with attached leaf ornamentations, piping or fluting. The frames are bole gilded.

See also examples of frames from the period of Ludwig XVI. |

|

|

|

| Germany, profile frame, 1st half 19th century. The broad, hollowed chamfer is decorated with a delicate palmette frieze and the sight edge with heart-shaped foliage. Due to a bevel cut at the rear, the frame appears to float in front of the wall. Model 1010 |

Germany, profile frame,

1st half 19th century. The rails of the frame are fluted, i.e. adorned with “cannelure” – grooves – that were carved into the whiting base before gilding. Model 988 |

||

|

|

|||

| Art Nouveau / Modern | |||

|

In Art Nouveau idiosyncratic frames, created by the artists themselves, (Gallen-Kallela, Munch) were developed alongside styles of frames that were designed by the art designers of the newly founded workshops for arts and crafts in Munich, Dresden and Vienna (Riemerschmidt, Pankok et al.). In buildings conceived by artists as complete objects of art in themselves, pictures (frescos, mosaics) were integrated into a spacious, geometrical wall structure. For frames from the vicinity of the Vienna workshops, gilded wave profiles are characteristic. With the start of the Modern period, the complex and expensive Art Nouveau frames were no longer in demand. Members of the “Blue Rider” and later the representatives of the New Objectivity movement preferred a simple wooden frame (Cassetta frame or moulded frame) without any ornamentation at all. After the 2nd World War, pictures were increasingly framed only with an atelier frame, or a simple wooden slat lying even with the surface of the picture.

|

|

|

|

| Germany, Cassetta frame according to a design by Franz von Stuck (1863-1928), 1st half 20th century. Example of a flat-linear Art Nouveau frame at the threshold to Modern: Gilded, fluted fillets divide the frame into segments. The colour of the surfaces subdues or emphasises the colour of the picture. Model Stuck 1 |

Germany, moulded frame for a picture by August Macke (1887-1914), 1st quarter 20th century. With the start of the Modern period simple wooden frames without any decoration came into being. The Expressionists preferred dark hues for their colourful pictures, sometimes set off with a narrow, silver or gold profile. Model Macke |

||